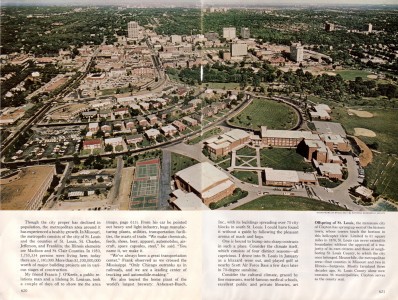

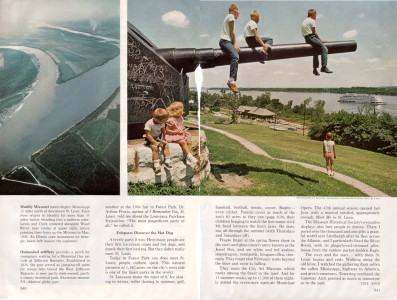

St. Louis, approved Missouri is a river city that’s spent hundreds of years trying to ignore its genesis by blotting out the unignorable. But there’s a remote section of North St. Louis County that has to end because the river says so. And in that wilderness are a few folks who don’t pay extra for a bluff-side river view because it’s part of their backyard.

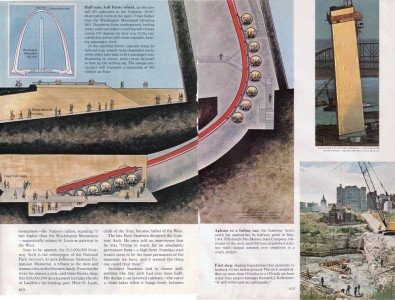

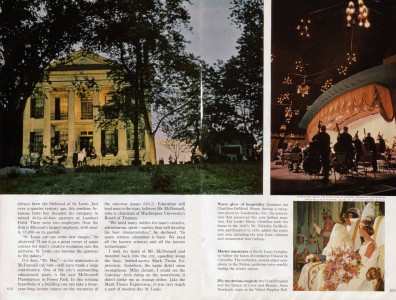

Head out New Halls Ferry Road in deep Florissant and you’ll come to Shackelford Road. While at that stop, page look across the intersection to the left and see the last remains of the once-grand entrance to the Desloge Mansion, now a weedy, gravel road blocked off with a utilitarian metal gate. Then continue up New Halls Ferry, where you will come to an undeniable line of demarcation between mannered society and where the river reigns. The house above, ancient but occupied, is the welcome mat to a stretch of road engulfed by trees, and where most everyone has made the wise decision to live on the hilly side because to live on the other side is to be a part of the river more times than a body can be comfortable with.

But there are 4 remaining homesteaders who did build on the other side of the road, smack against the thin lip between blacktop and river. For about 8 months out of the year they are hiding behind water-logged forestry, shadowy even on the brightest day. There is no sidewalk, so you can’t casually stroll by and observe these stubborn souls living where no one else has the guts to. And it’s no exaggeration to say that if you did make the choice to traipse through the mossy mud on their side of the road, a shotgun blast warning could be a standard feature.

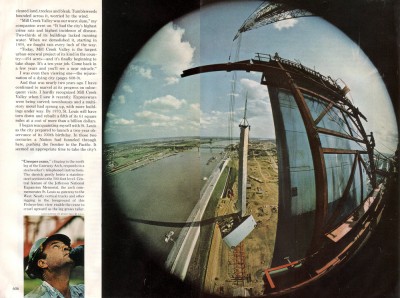

New Halls Ferry Road ends at the straight where the Missouri River seems to be logically heading toward a union with the Mississippi River in what would become Elsah, Illinois, but a radical change of mind caused it to high tail it out of there. But the Mississippi – a river that was having second thoughts about committing to a southerly direction – took chase after the Missouri, cornering it about 13 miles to South East. A Confluence was born, and then the Mississippi River runs down stream to New Orleans.

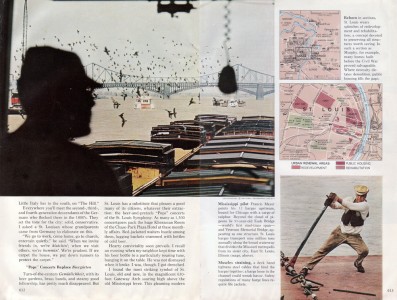

Look at this map and see that New Halls Ferry was making a crazy beeline into the river before it thought better of such a foolish notion.

Right at this point is the easiest and quickest public access into the churning brown waters of the Missouri. A casual stroll can turn into a suck down into the undertow. For a short spell we lived less than a half mile from this point, up Douglas Road.

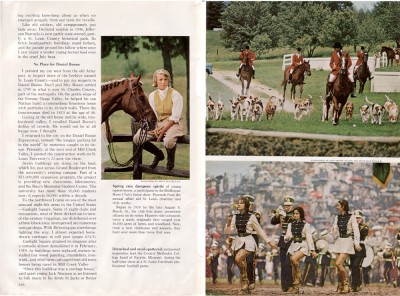

I was waiting to start 1st grade, so to a young girl coming from the dense, inner ring suburbs of Jennings and Ferguson, this was a wonderland of endless forests, swarms of lightning bugs brighter than the dusk-to-dawn lamp post in the front yard, a loping Trouble puppy and my first Sugar pony trotting alongside a red gelding named Rusty in the back yard horse paddock.

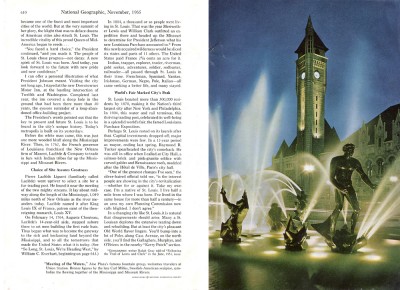

But during our two years, there was a late summer locust invasion that thoroughly freaked out my thoroughly Soulard urban mother, livestock along this stretch of river road were poisoned to death in a personal vendetta, and dead bodies were dumped onto that last sliver of land between the road and the river.

North Countians over a certain age still recall the 1971 murder of two Radio Shack employees abducted after they closed up shop. I remember watching my folks bid goodnight to guests as the Channel 4 evening news followed the nightly “It’s 10 o’clock – do you know here your children are?” with the report that their bodies had just been found in the woods between New Halls Ferry and the Missouri River. That’s right down the street! We all shivered at the thought of the closeness of depraved souls wading into places we knew you should never go, rolling bodies into the deep, damp unknown.

I lingered on the thought of detectives gingerly stepping through rotted trees and underbrush in the ominous cold indigo with nothing but flashlights, looking for something grisly, second-guessing their line of employment. I couldn’t fall asleep that night, and for every night after that, as another murder was reported, I was sure their body was laying 2,500 yards from our house.

A North County rite of passage is the legend of the Bubble Heads, who seem to exist in all those pockets where land gives way to river, as if the unrelenting humidity swells the heads of the unhinged. They claim that Bubble Heads were along this stretch of New Halls Ferry. I’d rather run into one of those mythical creatures than the real world facts of murdered bodies – known and unknown, human and bovine – that have littered the area. They claim the ghosts of young boys who drowned in the long- abandoned quarry (right before you get to the still-operating quarry) can be heard as the sun sets. All of it adds up to a low hum of ominous that affects even those who know nothing of the area until they stumble upon it during a Sunday drive.

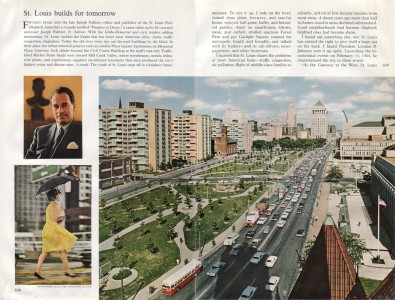

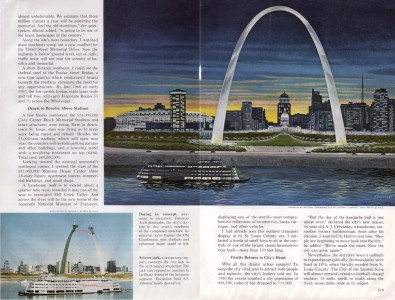

Passersby who notice these abodes tucked behind the trees in front of the river comment on their rumpled state. But as with any riverside community, there is an acceptable level of decay, because you can’t stop Ole Man River from peeling your new paint job and curling your wood siding. For these 4 homesteads along New Halls Ferry, they probably have to sweep river water out the basement after just 2 days of steady rain, so what’s the point of being overly manicured when the river will always chew your nails to the quick?

For the 1910 home above, if someone has a good throwing arm, they could lob a baseball into the Missouri from the back porch. They’re sited so close to the road because they had no other option. But year after year, the option to not live there doesn’t seem to cross their mind, except when the river and old age has eroded a home into the ground.

During the last 40 years along this short stretch of road hugging the river, once occupied land has reverted to vacant swamp, but the family still holds the property rights. Unlike the flood-prone portions of, say, Chesterfield Valley, developers aren’t clamoring to build new upon the unbuildable. When the sound of the river can sometimes drown out the TV with the windows open, logic prevails in the hearts of those not cut out to live on the river.